Notes from the Executive Director – December 2022

Planning Climate Resilient Neighborhoods Needs to Be Washington State’s Next Climate Policy Priority

My partner Matthew is thinking about selling his Toyota Tacoma truck. It’s 20 years old, but he’s kept it in good shape. We are lucky to live in a neighborhood where we just don’t use it that much, so why keep paying for the insurance, the tune ups, the tabs, the parking permits?

As we close out 2022, I’ve been reflecting on this little household financial decision as it relates to the climate crisis. Climate advocates like me have a lot to celebrate, especially here in Washington State. I honestly thought I would never see meaningful climate legislation pass Congress in my lifetime, but this summer the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) rose like a clean energy phoenix, supercharging incentives for wind and solar power, heat pumps, electric vehicles, and more.

This surprising federal win follows several years of landmark legislation here in Washington State. The Clean Energy Transformation Act is creating a path to a zero-carbon utility grid. A new clean fuels standard will reduce climate pollution from each mile we drive. The Climate Commitment Act will fund huge investments in the infrastructure we need to transition to a cleaner economy. And just this week, Governor Inslee announced that we will join California to make all new cars electric by 2035.

At the same time, the surge in gas prices earlier this year was a stark reminder of how integral fossil fuels remain in our daily lives. I felt the political whiplash watching President Biden beg Saudi Arabia to increase oil production at the same time he was championing the IRA, his approval rating bobbing up and down with the price at the pump.

Transportation is our largest source of greenhouse gas pollution. We have increasingly built our communities around cars. We now drive twice as much as we did in 1970 and a lot more than the rest of the world. Our growing dependence on our cars to meet our most basic needs remains our greatest obstacle to completing the rapid and just transition to clean energy that our planet and our communities desperately need.

Cleaner fuels and electric cars are essential, long-term parts of the solution. Ending sales of gas-powered cars by 2035 is a great and ambitious policy, but even if all new cars are electric starting in 2035, the complete transition of our vehicle fleet will take many more years. The average American keeps their car for 8 years, but many, like Matthew, keep theirs for longer. When it does come time to replace an old car, lots of people can’t afford new cars. Many will buy used, gas-powered cars after 2035. Even when we do eventually get an all-electric vehicle fleet, if we keep driving further every day due to displacement and urban sprawl, there is no guarantee we can build all the renewable energy we will need to cleanly power those extra miles.

Let’s take a look at what is happening in California. They are several years ahead of us, implementing enhanced vehicle efficiency requirements in 2009 and a low carbon fuel standard in 2011. These policies have continually been strengthened and they have achieved their intended purpose, increasing average miles per gallon for gas cars and spurring rapid growth in electric vehicle sales. However, if you look at the state’s overall emissions from transportation, those benefits have been mostly offset by increases in driving. We run the risk of falling into the same trap.

If we want to meet our emissions reduction goals, we need to combine our ambitious efforts to electrify vehicles and clean our fuels with equally ambitious efforts to reduce the need for driving so many miles every day.

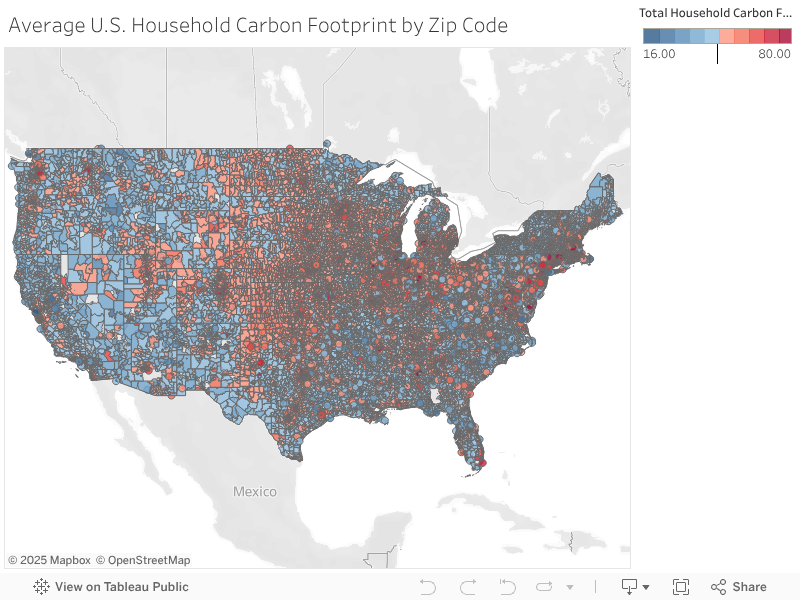

How much we need to drive is largely dependent on where we live and how we design our communities. This is vividly illustrated by newly updated maps from the New York Times and the UC Berkeley Cool Climate Network.

In cities and towns, a moderately dense mix of homes, jobs, goods, services, and gathering spaces creates proximity to more of the places we need to go. People oriented buildings and street design make walking safer and easier. Frequent transit service connects these communities to each other. Together, proximity, walkable neighborhoods, and frequent transit service are powerful tools for reducing driving. We also need to ensure that everyone can afford to live in these neighborhoods and enjoy these benefits without getting displaced.

Creating people-oriented neighborhoods doesn’t mean banning cars. It means spending less time in your car. It means investing more in places and less in moving through them. Growing our existing cities and towns in this way also protects our rural areas, which the same map shows are also less carbon intensive.

Think about your historic small town main street or your city’s pre-war streetcar neighborhood. We used to build all our neighborhoods this way. But as the Times article above explains, “For decades in the United States, the majority of new homes have been built in the suburbs and, increasingly, exurbs, where climate footprints are larger. As a result, for many people today, it is often easier and cheaper to find a home in a high-emissions community than a lower-emissions one.”

We need to learn from our own history and from other parts of the world. When we design neighborhoods around people instead of cars, we don’t just reduce climate pollution, we unlock a whole host of co-benefits that improve our health and our local economy, creating thriving communities now and for years to come.

I feel lucky to live in a neighborhood where my family doesn’t need our car. Right now, that’s a rare privilege in Washington State, but it doesn’t have to be. This coming legislative session we have an opportunity to put ourselves on a different path by adding climate change to the state growth management act (GMA), our state’s framework for how we grow. Futurewise and our many allies came so close to making that a reality last year. This coming legislative session the Governor and leaders across the environmental community are joining us in making climate in the GMA a top policy priority. But we also need your help. Please consider signing up to volunteer and making a donation.

And if anyone is looking to buy a 2002 Toyota Tacoma, you know where to find me.

Alex Brennan